BUSINESS AS USUAL

First-year Final Critique Installation

Throughout history, landscape representations have depended on a poetic sensibility—one that tied scientific and aesthetic approaches to veil the ideological politics behind their production. Business As Usual brings together the research-based work I produced during the first year of my MFA.

By focusing on the art produced during military expeditions of the American Southwest, I consider the histories of conquest embedded within art production. Recognizing that art has been employed to invent and maintain the idea of “The West” and make it serve imperial and capitalistic processes, my work wishes to denounce these ideologies must reimagine how to represent these lands. As such, I engages the traditions and conventions of aesthetic landscape representation with the intention of distorting and interrupting them and expose their ideology of power.

By focusing on the art produced during military expeditions of the American Southwest, I consider the histories of conquest embedded within art production. Recognizing that art has been employed to invent and maintain the idea of “The West” and make it serve imperial and capitalistic processes, my work wishes to denounce these ideologies must reimagine how to represent these lands. As such, I engages the traditions and conventions of aesthetic landscape representation with the intention of distorting and interrupting them and expose their ideology of power.

RESEARCH

The punitive 1849 expedition by the US Army against the Navajo and Utes Nations provides us with a case study to examine the ways in which landscape representations were employed to incorporate new areas of “the West” and to dispossess Indigenous and Mexican peoples of said lands in the age of Manifest Destiny. My intention is to make direct connections between official legislative policies of the 19th century and the artistic genre of landscape art—to make evident the violent histories of US exploration, expansion, and exploitation in the seemingly placid categories of the sublime and the picturesque.

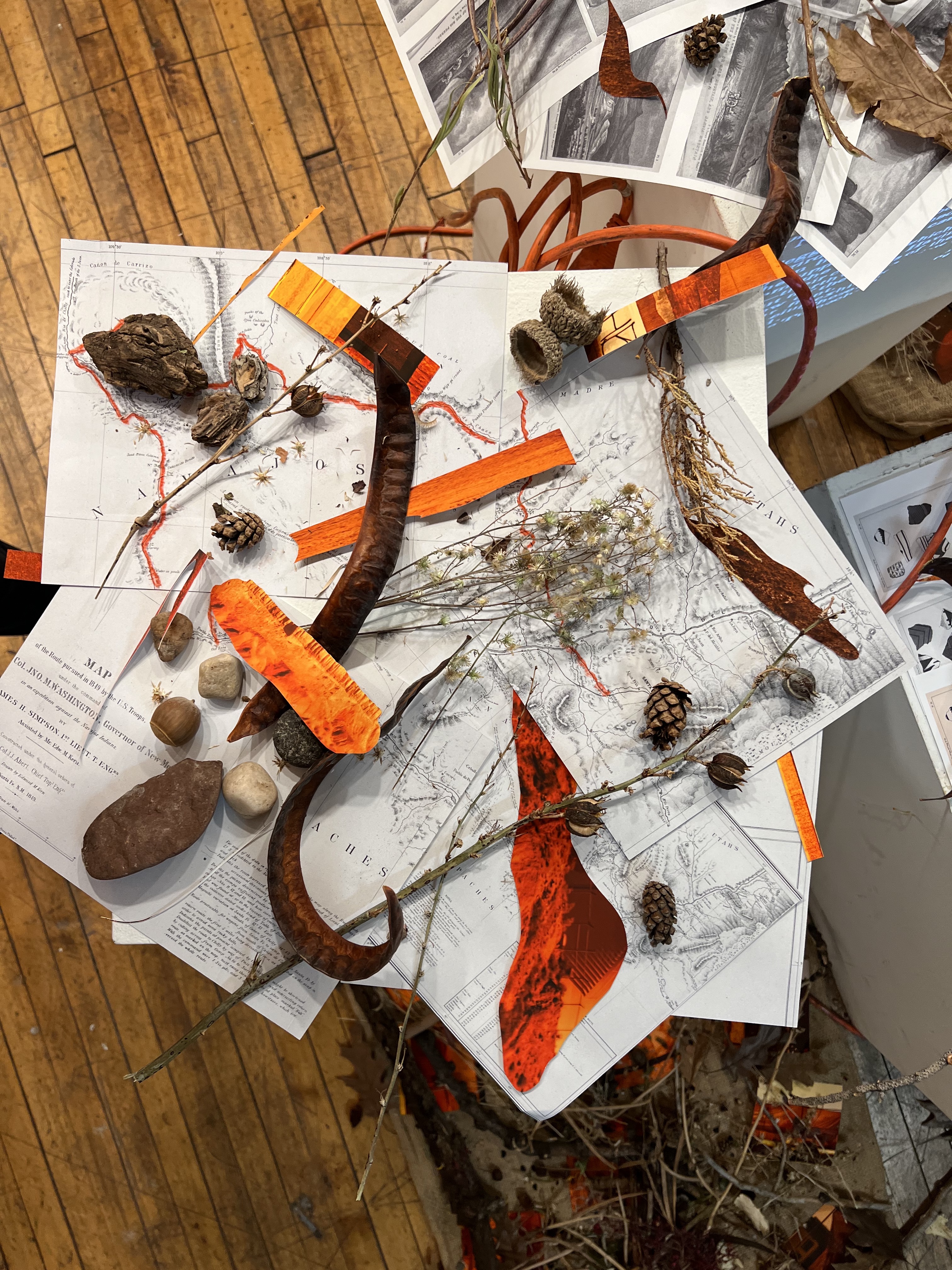

The material evidence produced during this particular expedition—James H. Simpson’s journal, Richard H. Kern’s sketches-turned-lithographs, and Edward M. Kern’s map—are all representations of the Southwestern landscape that reaffirm “discovery” as a white and Christian endeavor that ignores but simultaneously is made possible only by the aide of previous inhabitants. Accompanying the expeditions were Pueblo, Navajo and Mexican guides, scouts, and members of the volunteer militia whose very presence and expertise allowed for a cognizable “discovery” of the land.

![Map of the Route pursued in 1849 by the U.S. Troops […] in an expedition against the Navajos Indians](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/f0815349f1eb43456d55c4dd6f72ae09a64e606fe52d85fa357b280c054de32e/MAP.png)

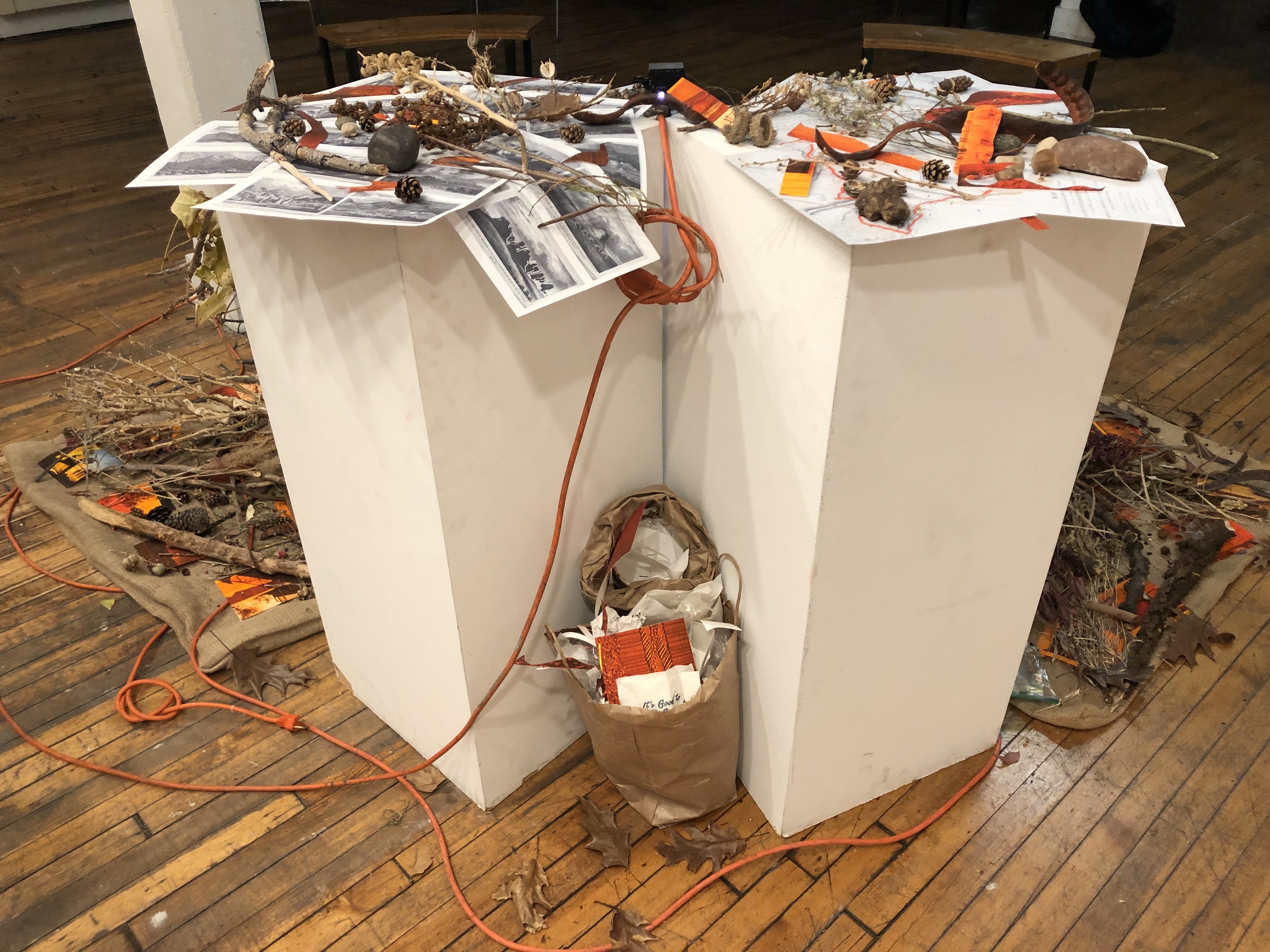

INSTALLATION

E.M. Kern’s Map of the Route pursued in 1849 by the U.S. Troops […] in an expedition against the Navajos Indians is the foundation of Business As Usual. This cartographic landscape traces a 587.11-mile-long loop through modern-day New Mexico and Arizona. The map will be the navigating document in the gallery—however, audiences will not be retracing the troop’s steps; rather, they will retrace the ideology that made the expedition possible. In this manner, the gallery itself a becomes an artificial three-dimensional landscape representation.

The walls will be “layered” to represent three key elements of landscape art: (1) the background, (2) the foreground, and (3) the middle ground.

(1) The layer closest to the wall represents the background; and cartography will be the main element here. The act of surveying and mapping land exemplifies the taking a natural space and forcing it to fit onto a two-dimensional piece of paper. On the map, a solid red line represents the route taken by US troops as they surveyed. I will take this red line and copy it onto the walls, scaling to make it fit around the whole room. The result will be a seemingly abstract red line that wraps around the walls of the gallery. Understanding cartography as a distorted representation of space, my red line will be a distortion of a distortion.

(2) The wall layer closest to the viewer will represent the foreground and will be composed of 8-feet long panoramic collages. These panels will be a tryptic, altogether approximately the width of two freeway lanes (24 feet). I collage Southwestern highway wall art with deconstructed landscape photographs taken frenziedly through a moving car window. Geographically, the images document freeways and landscapes in Arizona, California, Chihuahua, Nevada, New Mexico, Sonora, Texas, and Utah. Just as the freeway walls obscure our view while driving, these collages will also be symbolic obstacles to our sight in the gallery. As the most prominent aesthetic element (deceptively so) in the gallery, these collages are intended as diversions from what I consider the most important element…

(3) As a key concept in landscape conventions, the middle ground is the site where ideology takes place. It sharpens and delivers the message; land as resource, land as wealth, land as power. The middle distance obscures “the fundamentally destructive character of settlement”—where the conflict between civilization and nature is visually reconciled.[1] Here, time-based media introduces a new conceptualization of the land; collapsing past and present and merging different imaging technologies. Sonically, archival narrations of the land and contemporary reviews of tourist destinations center the sublime as the experience that gives meaning and worth to the Southwest aridlands—showcasing the sublime’s historical evolution going from residing in nature to large-scale industrial projects that litter the land.

Overall, the aim is to reveal how aesthetic landscape conventions have been complicit in silencing the violence of colonization, dispossession, and racialization of Indigenous, Asian, and Mexican subjects—presenting us, instead, with a charming encounter with “the land of enchantment.”

[1] Miller, Angela. The Empire of the Eye.

OBJECT IMAGES